“Divest, transitive verb: 1) To strip, as of clothes. 2a) To deprive, as of rights or property; b) to be free of. 3) To sell off or otherwise dispose of.”

The word leans both positive and negative. To strip, or to deprive: that’s harsh. To be free of—oh joy!

If we’re blessed enough to live into old age, it’s time to strip. And be free.

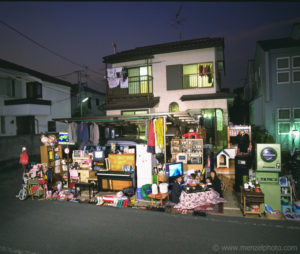

There’s a book called Material World: a Global Family Portrait. The author/photographer went around the

world persuading families to empty their houses of all durable goods: appliances, dishes, books, clothing, furniture. The Ukita family stack their possessions as compactly as their tidy apartment along the sidewalk in front of their building. The Natromos of Mali—nine kids and three adults—smile from their rooftop surrounded by earthenware pots and utensils. Most of their clothes are on their backs. In northern California, the property of Regan Ronayune and Craig Cavin and their two kids sprawls across their suburban lawn: tools, toys, and toddler ware, necessities and luxuries tumbled together.

Every American house is like a little American frontier: empty space to be filled.* We tend to fill up the space we have, and then some—observe the boom in separate storage units.

Periodic moves help to clear away some of the underbrush. My husband and I moved 23 times in our first 25 years. For our early moves we got all our stuff in a pickup truck and a VW bug. For our last move, we required one-third of a cross-country Bekins trailer. At every stop on the way to our current location we filled up more space.

As for our current location, we’ve been here twenty years—long enough for the tide of our lives to turn. What that means is, it’s time to divest.

Reason one: Stuff persists. As the years pass, a kind of stratus-layer buildup takes place. The file cabinets and understair storage areas and those closet shelves that aren’t easy to reach harden like anonymous stone. What’s in there? I don’t even know anymore. Maybe detritus from my mother’s estate, or mother-in-law’s, squirreled away before I could figure out what to do with it. Like bad cholesterol in the bloodstream it’s not going away and will make itself known at some inconvenient time.

Reason Two: My kids don’t want our stuff. The inconvenient time may be when I croak, or take a serious turn for the worse, like a debilitating stroke. That’s when my children, who now have lives and families of their own, get the unwelcome responsibility of divestment dropped in their laps. In the old days, family possessions were handed down through two or three generations. Daughters may actually have wanted a grandmother’s silver, but now—who uses silver? or much less, china? Not only is cheap merchandise readily available, but tastes have broadened. Don’t assume your kids want your four-poster or steamer trunk. Ask if they do. If the response is less than enthusiastic, dump it. Let them miss you for your thoughtfulness and personality, not for the job you saddled them with.

Reason Three: The direction is toward less, not more. Tiny houses may be a short-lived fad (easier to

admire than to actually live in), but the culture is scaling down, for reasons not entirely good. (It’s fine to want to get by with less stuff; not so fine to get by with fewer babies). For now, though, that’s the trend: digital vs. material, disposable vs. durable, temporary vs. permanent.

Reason Four: Freedom. Old age is the time to go deep rather than wide. To spend down portfolios and build relationships. To men what’s broken and appreciate what isn’t. To number the days and spend them wisely. Possessions become a burden the minute you no longer need them, or when your arthritic hands can’t wrangle the scissors or your fumbling brain can’t remember how to use the tools. I’m not that old yet, but it’s time to start loosening my grip, singer by finger. Soon enough I’ll have to let go.

Divest. Do it while you’re still able. Then enjoy your freedom.

*Meaning no disrespect to Native Americans; I know they were here first. But they didn’t fill up the place.

around her, take stock of what she had, and be grateful for it. In time she gave hundreds of American women reason to be grateful too.

around her, take stock of what she had, and be grateful for it. In time she gave hundreds of American women reason to be grateful too. She always said—and sincerely believed—that a woman’s chief place was in the home, but she saw that place as a noble calling rather than thankless drudgery. She was, it’s fair to say, the Oprah of her day. Who can tell how many women felt lifted up and encouraged by the earnest editor of their favorite magazine?

She always said—and sincerely believed—that a woman’s chief place was in the home, but she saw that place as a noble calling rather than thankless drudgery. She was, it’s fair to say, the Oprah of her day. Who can tell how many women felt lifted up and encouraged by the earnest editor of their favorite magazine? decade:

decade:

Take “reflection.” Aside from the myth that gives “narcissism” its name, this form of idolatry is a cartoon image, the smitten individual gazing at himself in a mirror while surrounded by fluttering hearts. We’re too sophisticated for that, or almost. I’m old enough to remember a video that made the rounds during the 2004 election: John Edwards, the Democrat candidate for V-P, taking 14 minutes to comb his hair in front of a mirror just before his one televised debate. (To be fair, he possessed exceptional hair.)

Take “reflection.” Aside from the myth that gives “narcissism” its name, this form of idolatry is a cartoon image, the smitten individual gazing at himself in a mirror while surrounded by fluttering hearts. We’re too sophisticated for that, or almost. I’m old enough to remember a video that made the rounds during the 2004 election: John Edwards, the Democrat candidate for V-P, taking 14 minutes to comb his hair in front of a mirror just before his one televised debate. (To be fair, he possessed exceptional hair.)