“C. S. Lewis? Love him. Absolutely L-O-V-E him. I grew up with one foot in Narnia, you know, and Mere Christianity opened my eyes to the glory of faith. Till We Have Faces should be on everyone’s reading list. I’m not as fond of his science fiction, though I liked the first two novels of the Space Trilogy well enough. But That Hideous Strength? After the first few pages I had to put it down. I mean, what the heck . . . .”

In the summer of 1945, George Orwell wrote a review for the Manchester Evening News, beginning,  “On the whole, novels are better when there are no miracles in them.” That said, he was ready to give a grudging thumbs-up to C. S. Lewis’s latest work of fiction, which completed the trilogy begun with Out of the Silent Planet and continued in Perelandra. Orwell summarized the story as “the struggle of a little group of sane people against a nightmare that nearly conquers the world. A company of mad scientists—or perhaps they are not mad, but have merely destroyed in themselves all human feeling, all notion of good and evil—are plotting to conquer Britain, then the whole planet, and then other planets, until they have brought the universe under their control.” He describes it as essentially “a crime story, and the miraculous happenings, though they grow more frequent towards the end, are not integral to it.”

“On the whole, novels are better when there are no miracles in them.” That said, he was ready to give a grudging thumbs-up to C. S. Lewis’s latest work of fiction, which completed the trilogy begun with Out of the Silent Planet and continued in Perelandra. Orwell summarized the story as “the struggle of a little group of sane people against a nightmare that nearly conquers the world. A company of mad scientists—or perhaps they are not mad, but have merely destroyed in themselves all human feeling, all notion of good and evil—are plotting to conquer Britain, then the whole planet, and then other planets, until they have brought the universe under their control.” He describes it as essentially “a crime story, and the miraculous happenings, though they grow more frequent towards the end, are not integral to it.”

That Hideous Strength could be described as the crime story: the ultimate crime against humanity. In The Abolition of Man, published two years before THS, Lewis remarked on the rise of scientism (science as ultimate truth) expressed in the idea of “man’s conquest over nature”: “From this point of view, what we call Man’s power over Nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with Nature as its instrument.” Every scientific advance comes at a cost, ironically in the same area of its benefit: computer technology increases our knowledge while it curtails our comprehension; embryonic stem cell research promises to enhance life while at the same time commodifying it. As knowledge grows more specialized and esoteric, fewer and fewer individuals have access to it, and those will be the few who can control the many.

Orwell had thought long and hard about this; at the time of this review, he was probably already working on his masterpiece, which would be published three years later. 1984 addressed the same theme from a materialist point of view—no miracles. In his view, and we would all probably agree, man has enough cussedness in him to bring about a totalitarian world all by himself, without demonic help.

But Lewis, in the first two volumes of the Space Trilogy, had already grounded the good vs. evil conflict in supernatural terms. The basic problem goes way back: back to the garden. The power-grabbing government agency in That Hideous Strength, which takes over a small university town and plots to seize control over human evolution, is an echo of Babel (subject of the late-medieval poem from which the novel takes its title). Time and time again, human authorities try to seize ultimate power, which always resorts to Orwell’s definition of totalitarianism: “a boot smashing a human face, over and over and over.” But Orwell could offer no reason why this is wrong. Why shouldn’t the strong subdue the weak? It seemed to be the way nature worked.

Lewis could say why this is wrong: It’s because humanity is made in God’s image, a little lower than the angels, the object of a massive, age-old, ultimately successful rescue operation. A miraculous rescue. That’s why THS ends positively, while 1984 is a total downer.

Lewis could say why this is wrong: It’s because humanity is made in God’s image, a little lower than the angels, the object of a massive, age-old, ultimately successful rescue operation. A miraculous rescue. That’s why THS ends positively, while 1984 is a total downer.

Published immediately after a totalitarian attempt that wrecked Europe (World War II), squarely in the center of another one that threatened both Europe and Asia (Communism), both novels seemed painfully relevant at the time. But they still are. The steely, gleaming, soulless utopia imagined in 1950s sci-fi hasn’t quite developed as expected, but sales of 1984 hit bestseller status on Amazon for months after Donald Trump’s election. Alarmists on the left saw the rise of Big Brother. That was silly, but there’s more than one way to steal human freedom. Orwell’s dystopia is ruled by government intimidation;  Lewis’s near-dystopia is ruled by scientism. Our own world is apparently up for grabs. The federal government, by seizing more power for itself, threatens to kill by kindness, i.e., “taking care” of us until we’re drained of initiative. All of these systems diminish humanity by aggrandizing themselves.

Lewis’s near-dystopia is ruled by scientism. Our own world is apparently up for grabs. The federal government, by seizing more power for itself, threatens to kill by kindness, i.e., “taking care” of us until we’re drained of initiative. All of these systems diminish humanity by aggrandizing themselves.

_______________________________________________

The action of That Hideous Strength takes place after the first two volumes of Lewis’s space trilogy, but appears to have absolutely no relation to them (at first). That’s why you can read it independently, with only a passing acquaintance with what happened earlier. So here’s a passing acquaintance:

In Out of the Silent Planet, Dr. Elwin Ransom, professor of linguistics, is kidnapped and carried aboard a spacecraft to Mars. His kidnappers are Dr. Westin, a brilliant physicist, and Richard Devine, scion of nobility and a former classmate of Ransom’s. Westin’s interest in Mars is humanistic—he’s looking to conquer the planet for the perpetuation of the human race. Devine is only interested in profit. They intend Ransom as a human sacrifice to appease the alien life forms, but they’ve misunderstood what the natives want. On Mars (whose inhabitants know it as Malacandra), Ransom escapes his captors and becomes acquainted with the three societies of intelligent beings. He also learns Old Solar, the interplanetary language, and recognizes that Malacandrians worship the same deity he knows on earth, only under another name. The planet is ruled by an eldil (angel), whom he meets at the climax of the novel. Westin’s plans for conquest fail, and the three men are allowed to make a perilous return to earth.

Malacandra is a much older civilization than Earth, but Perelandra (Venus) is brand new. In the second volume of the trilogy, Ransom is summoned by the eldila to this new world, where he meets “the green lady,” a being like himself (except for the color), only with an otherworldly beauty and dignity. This, he recognizes, is what Eve was like before the Fall. Trouble arrives in the form of Dr. Westin, whose goals have shifted from his simpler chauvinistic designs toward Malacandra. Ransom can’t quite figure out what Westin is after until a potential Fall narrative develops with Westin playing the role of the snake and Ransom as . . . what? By the time he realizes that Westin has been possessed by a malevolent power, it’s almost too late to stop him. But Perelandra is saved by the narrowest of margins and heroic action by an ordinary man who becomes a hero. Ransom returns to earth triumphantly, but with a wound on his heel (see Gen. 3:15). (Perelandra had a profound effect on me the second time I read it; I wrote about that experience here.)

Ransom’s space adventures take place sometime during World War II; That Hideous Strength opens a few years after the war (during which corrupt men have moved to consolidate their power), and never ventures beyond our own atmosphere. No spaceships hidden in barns, no alien creatures or eldila; just a rather commonplace academic couple and a quick, less-than-invigorating plunge into campus politics. But in the first chapter, the lady has a very disturbing dream . . .

If you’d like to read along, I’ll cover four chapters per week with a commentary on Fridays. Four chapters may not seem like much, but they’re long—about 80 pages each—broken up into sections. My commentary will include notes about historical references, novelistic elements, and sections you might want to skip. Though I’ve been taken to task for recommending skipping, Lewis himself wrote, in Mere Christianity, that it was okay to pass over sections or chapters that had no relevance for you.

The problem with THS for American readers is that he freely indulges his “expository demon” and goes off on long tangents about English history, mythology, and legend that we know nothing about. It would be like me breaking off my narrative about early Hollywood in I Don’t Know How the Story Ends to get all misty-eyed over ballad-singing in medieval castles—not entirely unrelated, as movies and ballads are both forms of storytelling, but (speaking of stories) you’d really like to get along with the one you were reading. Those who have never been able to get through Moby Dick will know what I mean. But underneath the verbiage is Lewis’ most suspenseful, gripping, even cinematic narrative.

If you have any thoughts about the reading, please comment. I love talking about books. Also, what strikes me may not affect you the same way. FadedPage.com has a .pdf version of That Hideous Strength you can download to your tablet for free. It’s August: traditionally a long hot month, so find yourself a shady tree, get a glass of lemonade or ice tea, and let’s do some reading.

We get started with That Hideous Strength: The Setup.

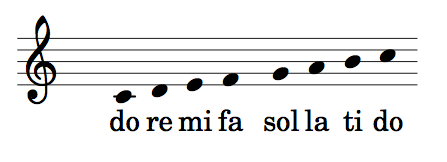

The Trinitarian God is neither noun nor verb; if we’re speaking in grammatical terms, he is a sentence. He even expresses himself as a sentence: I am. In him is the thought, and the meaning of the thought, and the shared understanding between the thinker and the meaner.

The Trinitarian God is neither noun nor verb; if we’re speaking in grammatical terms, he is a sentence. He even expresses himself as a sentence: I am. In him is the thought, and the meaning of the thought, and the shared understanding between the thinker and the meaner.

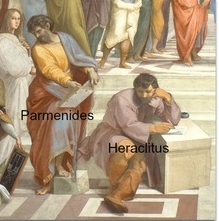

Besides paranormal sexiness, change was the attraction, as it is for every soap. Every single day brought new plot developments and twists and secondary characters tracing their arc across umpteen episodes. Would she, won’t he, could she, will he—and suddenly I realized that the show had no being, only becoming. Barnabas’ story would never resolve; nor Quentin’s. Just endless cycles until, like me, everybody got fed up. Dark Shadows was a smashing success for about two years. When the novelty wore off the mechanics of change-for-the-sake of-change were exposed for all to see. Other soaps, like Days of Our Lives and General Hospital ran on the same principle, but doctors and rakes and gamblers and vamps have more than one trick up their sleeves, and could keep an audience guessing longer than vampires and werewolves.

Besides paranormal sexiness, change was the attraction, as it is for every soap. Every single day brought new plot developments and twists and secondary characters tracing their arc across umpteen episodes. Would she, won’t he, could she, will he—and suddenly I realized that the show had no being, only becoming. Barnabas’ story would never resolve; nor Quentin’s. Just endless cycles until, like me, everybody got fed up. Dark Shadows was a smashing success for about two years. When the novelty wore off the mechanics of change-for-the-sake of-change were exposed for all to see. Other soaps, like Days of Our Lives and General Hospital ran on the same principle, but doctors and rakes and gamblers and vamps have more than one trick up their sleeves, and could keep an audience guessing longer than vampires and werewolves. hindered from coming, and that they possess some quality that preeminently suits them for membership in the kingdom of God. You’ve heard sermons on the “for such belongs” part, so I won’t dwell on it here. I’m interested in “Let them come” and “do not hinder.” Two questions: Would little children freely come? And if so, how are they “hindered”?

hindered from coming, and that they possess some quality that preeminently suits them for membership in the kingdom of God. You’ve heard sermons on the “for such belongs” part, so I won’t dwell on it here. I’m interested in “Let them come” and “do not hinder.” Two questions: Would little children freely come? And if so, how are they “hindered”?

perfect circle, it struck him that the ratio of the two circles equaled the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn. What if all the planetary orbits displayed a similar geometric relationship? The hypothesis didn’t work out quite as well as he hoped, but speculation along this line led to Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion and the discovery that a) orbits are elliptical, not circular; b) a planet’s speed varies between aphelion (when it’s closest to the sun) and perihelion (its farthest distance from the sun); and c) the duration of any planet’s orbit depends on that planet’s distance from the sun.

perfect circle, it struck him that the ratio of the two circles equaled the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn. What if all the planetary orbits displayed a similar geometric relationship? The hypothesis didn’t work out quite as well as he hoped, but speculation along this line led to Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion and the discovery that a) orbits are elliptical, not circular; b) a planet’s speed varies between aphelion (when it’s closest to the sun) and perihelion (its farthest distance from the sun); and c) the duration of any planet’s orbit depends on that planet’s distance from the sun.

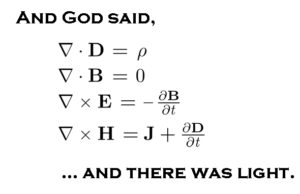

a surging mass of elements, or the back of a very large turtle. Ancient Egyptians, Sumerians, Africans, Meso-Americans and indigenous tribes the world over would have been quite puzzled at the idea of speaking light with no obvious light source. God doesn’t get around to creating the sun until Day Four—is this not an anomaly? So I asked, when old enough to understand what “anomaly” was.

a surging mass of elements, or the back of a very large turtle. Ancient Egyptians, Sumerians, Africans, Meso-Americans and indigenous tribes the world over would have been quite puzzled at the idea of speaking light with no obvious light source. God doesn’t get around to creating the sun until Day Four—is this not an anomaly? So I asked, when old enough to understand what “anomaly” was.