Infrastructure

/ ˈɪn frəˌstrʌk tʃər /

The Biden Infrastructure bill is getting a lot of criticism for what it isn’t—an infrastructure bill. That is, it’s only tangentially about infrastructure. Anywhere from 5-20% of the roughly $2 trillion goes to roads, bridges, and utilities—what we generally consider infrastructure. And not just us, but the dictionary too: “The basic facilities, services, and installations needed for the functioning of a community or society, such as transportation and communications systems.” Concrete, asphalt, steel, and wire, and the maintenance thereof—that’s what most people consider to be infrastructure. Or do they?

The Biden administration is thinking more creatively. I’m not going to argue on the virtues or venalities of the bill or why Congress should allocate $2 tril for it; I’m more interested in the terminology. To road-and-bridge maintenance, the administration adds

- “Care infrastructure”: money for elder and child care

- “Educational infrastructure”: money for building new schools

- “Human infrastructure”: money for job-training and union organizing,

- “Research infrastructure”: money for universities and think tanks (to come up with conclusions the government likes, says my cynical side)

- “Environmental infrastructure”: money for incentivizing electric cars and phasing out gasoline engines

We can argue about each item on the list—and there are a lot of items—and whether government bureaucracy is the best way to facilitate them, but (being a language person), I’m most interested in the way the administration is finding so many applications of the world “infrastructure.” They’ve stretched it to embrace anything the administration wants to do, thereby making it practically meaningless. This shapeless blob of a word now covers broad consensus (roads and the power grid should be adequately maintained) as well as ideological fringes.

Such terminology is perilous, in that it

- Blurs distinctions and definitions. This is a feature, not a bug, of postmodernism, which pretty much denies objective meaning. As an academic theory po-mo only harms students; as a governing philosophy it harms everybody.

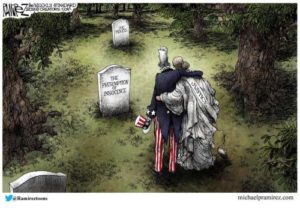

- Tends to make humans into a commodity: buying units to purchase desired products, workers to be trained, young minds to be conditioned, old people to be sidelined. American citizens become part of American “infrastructure.” And what does that mean?

“Infrastructure,” then, isn’t about asphalt and wire; it’s about forcing American society into a model favored by one end of the political spectrum. If everything is infrastructure, everything is subject to restructuring.

The campus free-speech battles going on now are based on a premise that speech is violence: sticks, speech, and stones break my bones. I think it’s interesting that those more sensitive to verbal violence use the most violent words: Nazi, Fascist, bigot, racist, and much worse. In the infamous

The campus free-speech battles going on now are based on a premise that speech is violence: sticks, speech, and stones break my bones. I think it’s interesting that those more sensitive to verbal violence use the most violent words: Nazi, Fascist, bigot, racist, and much worse. In the infamous