Ralph Moody isn’t as well known as Laura Ingalls Wilder, and didn’t occupy quite the same time period, but he accomplished something similar. My husband and I have been reading through his series of memoirs, which he began writing at the age of 50.

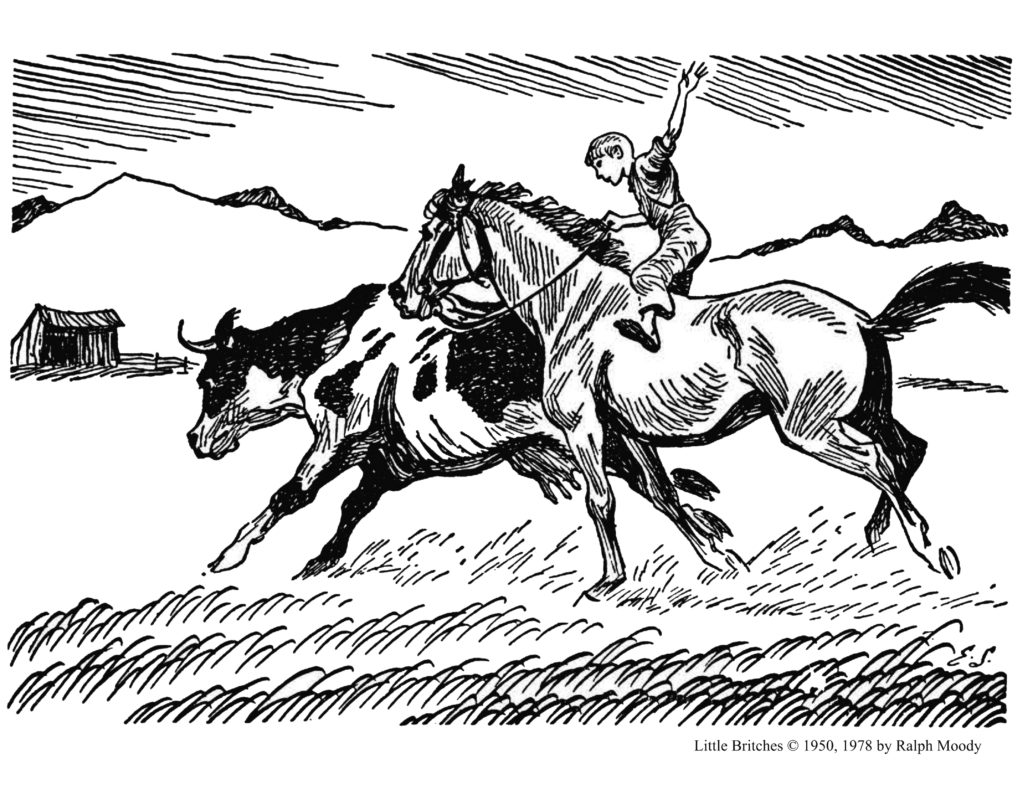

Born in 1898 in Rochester, NY, Ralph’s formative childhood was shaped in Colorado, where the family moved when he was eight years old. There the boy learned to rope and ride, acquiring the nickname “Little Britches” from the local cowboys. After failing at ranching, the Moodys settled in nearby Littleton, where Ralph’s father died as a result of a horse/auto accident. As the eleven-year-old Man of the Family, Ralph took odd jobs and organized the local boys into work teams, and even spent a summer working for a neighbor at The Home Ranch, receiving a man’s wages.

In 1912, for reasons too complicated to detail here, Ralph’s mother abruptly moved the family to her home state of Massachusetts. Starting over with almost nothing, Mary Emma and Company” established a laundry business while Ralph worked a number of side-hustles. All perfectly legitimate, but somehow he got the reputation of a troublemaker and at the age of fourteen he went to New Hampshire to work with his crotchety old grandfather in The Fields of Home. He didn’t get along with Grandfather, but that wasn’t entirely his fault; the old man didn’t get along with anybody.

When America entered World War I, Ralph worked in a munitions plant because the army judged he was too sickly to fight. His puniness was later diagnosed as diabetes, and the family doctor held out one hope for susvival: go west young man, get as much sun as possible, eat lots of green leafy vegetables, and don’t do anything crazy. He obeyed every rule except the last.

Not entirely his fault; the only job he could get upon his arrival in Arizona was performing “horse falls” for the movies. The hard-earned stake he gained from that brief venture began disappearing when he met Lonnie, an overgrown hyperactive kid who talked him into buying a Model T they nicknamed “Shiftless”—a total lemon. Nevertheless, the two young men tore across the Southwest, Shaking the Nickel Bush between breakdowns.

They were flat broke when Ralph hit upon his most productive money-making scheme yet: selling plaster busts to bankers and lawyers in small towns between Phoenix and Santa Fe. (He’d picked up that skill from an engineer at the munitions plant who sold sculpture on the side.) He converted the proceeds to fifty-dollar bills, which he carefully rolled up in the cuffs of his extra-long Levis. It amounted to almost $1000, with which Ralph intended to buy a little ranch and do what he liked best. Unfortunately, when he and Lonnie parted ways the latter absconded with the jeans. Ralph was sure (pretty sure) it wasn’t theft; Lonnie just snuck out in the dark with the wrong pants. And no forwarding address.

We’ve just started reading The Dry Divide, in which our hero hops a freight to Nebraska with one dime in his pocket. The back-jacket copy reveals he will end up with “eight horse teams and the rigs to go with them.” In the next and final volume, Horse of a Different Color, he will court his boyhood sweetheart and settle on a career.

All this, mind you, packed into 25 years: quite a ride, and yet probably not too unusual for the time. Ralph Moody’s America was an open society that allowed for amazing mobility, both up and down. For all his natural gifts, including ingenuity, creativity, and a cheerful disposition, he never made a lot of money and the lean times didn’t end with his marriage. But I doubt he regretted any of it, especially those early years which he recalled much later in loving, meticulous detail. He lived with eyes wide open, observing, remembering, and appreciating.

Though he carried a Bible with him, the family religion relied more on can-doism than Amazing Grace. “God helps those who help themselves” might have been the family motto (although it’s not in the Bible), and one senses more than a little pride in his mother’s determination to accept no help beyond what she absolutely had to. That might not be fair to Mary Emma, who endured severe hardship with amazing resilience and positivity, but she could be stubborn too. As could Ralph’s sister Grace, who could figure and dicker like a man but dropped out of school early because, as Mother said, she wouldn’t need any more education to make a home.

Unlike the Little House books, there’s no overt racism or hostility. “Coloreds” are not particularly numerous out west, and the only Indians Ralph meets are falling off horses for the movie cameras. (As rough as it was for them, it was a lot worse for the horses).

For good and ill, that America is gone: rough-and-tumble, snooze-you-loose, unpredictable, perilous, exhausting, and exhilarating. Racism, favoritism, cops and politicians on the take—nothing new about that. A generally honest, straightforward, enterprising, and upwardly-mobile populace—that was, if not new, then certainly rare. Will we ever see the like again? I wouldn’t bet on it.