I’ve been reading Isaiah this month, two chapters a day. Reading Isaiah is like riding a yo yo: up and down; up and down. The mood changes almost mid-sentence from righteous judgment to gracious reconciliation—but let’s start at the beginning.

The LORD strides upon the scene, calling out his grievance to the heavens and the earth:

“Children have I reared and brought up

but they have rebelled against me.” (Is. 1:2b)

This is the problem: the rest of Isaiah (and all the prophets, come to think of it) chew on that theme: Ah, sinful nation: sick desolate, ruined. These are the judgments of the Lord, but also the natural consequences of cutting themselves off from the very Creator who put the breath in their bodies. That breath remains and not only commits Israel to him, but commits him to Israel. He has bound himself to them, and difficulties immediately arise.

For the first four chapters (and throughout the book) a personality emerges that a psychiatrist would label schizophrenic. Reams of condemnation roll out, alternating with brief passages that look like the speaker is reconsidering: “Come, let us reason together . . .”

“. . . they shall beat their swords into ploughshares . . .”

“Zion shall be redeemed. . . ”

“It shall be well with the righteous . . .”

The weight of sin and rebellion drags the oracle down, down, down—but still it struggles to rise.

Chapters 5 and 6 forge a theme for the first “Book” of Isaiah (chapters 1-39). The case against “my people” is accurate and detailed and could apply to “our people” today. And if our people complain about His peevishness, vindictiveness, arbitrariness, and cruelty, here’s his answer:

The LORD of hosts is exalted in justice,

and the Holy God shows himself holy in righteousness.

He can’t be holy and righteous without judging. And he can’t judge without holiness and righteousness.

But—what about those people, whom he made and shaped and breathed immortal souls into? As the rock-ribbed Calvinists say, he has every right to send all of them to hell. There is none righteous; no, not one. But—

He has committed himself, by his very breath.

What to do?

That (speaking in purely human terms) is the Divine Dilemma. “Children have I reared and brought up . . .” Every parent with wayward children can sympathize. What do you do?

You don’t stop loving them—unless you never really loved them in the first place. If you saw your kids as an extension of yourself, intended to draw praise back to you for how well you raised them, it might not be that hard to cut them off: Sayonara, punk. You had your chance and you blew it.

But even if there’s a smidgen of love in your complicated feelings, there’s at least that much pain. Love is a risk. I might even say that love is risk. You’ve cut yourself open to admit the unknown; a being that brings its own complexity, hidden dangers, and uncertain future. And it turns on you. That which promised to complete you now claws at you and threatens your very identity.

God doesn’t need us for completion. Still, what do you do . . . if you are God? Two choices:

One, you let it go. Let the heedless children destroy your house, trample your rules, leave your righteousness in tatters. In the process they choke on their own autonomy and you cease to be righteous and thus no longer God. They’ve squandered their identity and stolen yours. Nobody wins.

Two: you exercise your righteous judgment, stop the oppression, punish the oppressors. You are still God, but your creation is stuck in an endless round of destruction and renewal (see the book of Judges) until it exhausts itself. Technically, you win . . . but not really, if your grand experiment reveals itself to be a failure and the fiery hallways of hell ring with Satan’s laughter.

Or wait—there’s a third option.

For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given . . . (Is. 9:6)

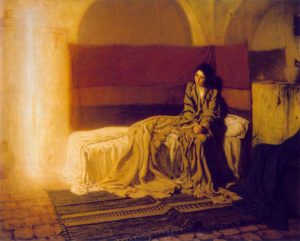

Higher criticism insists that this child is a contemporary born into the royal household, a brief uptick in Judah’s downward drift. But the extravagant language—Mighty God, Everlasting Father, etc.—is a bit much, even for court-flattery. The child the virgin conceives may be the son of a virtuous, recently-married young woman of Isaiah’s time. But there’s another Son, another sign given to a later virgin who wonders, “Wait . . . how can this be?”

Tucked among Isaiah’s fiery images and agonized and wrathful pronouncements wrung from Israel’s struggle with God, a Man emerges. A promised child, like Isaac and Samson; a sapling from the seed of Jesse like David; a servant and prophet like Moses, a sacrificial victim like . . . no one else.

He’s the third way, the resolution of an impossible dilemma and the reconciler of opposites.