Have you read White Fragility or How to Be an Anti-Racist? Even if you haven’t read them, you’ve probably heard of them. I’ve heard from WORLD readers who are making a good-faith effort to examine their own biases by exposing themselves to challenging points of view from the Times best-seller list. I applaud the motivation, but some of those books should come with warning labels: Ideas produced in the hothouse atmosphere of the modern university may not be profitable for the real world.

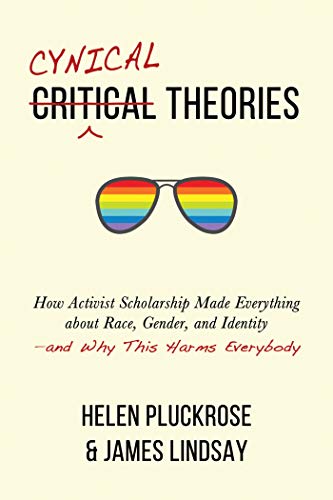

So don’t read those without reading this: Critical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race Gender, and Identity—and Why This Harms Everybody. Cynical Theories, by two academics who have been there, tracks antiracism to its source. Also radical feminism, post-colonialism, toxic masculinity, trans identity, genderqueerness, body positivity, fat shaming, and intersectionality. Even if you’re not aware of those things, they are aware of you, especially if you’re white, straight, and male. Or if you disagree with any proposition from the toxic well of Theory.

“Theory” is the broadest term for all the academic disciplines examining power and privilege. It’s rapidly expanding to embrace all the academic disciplines, including the hard sciences and mathematics. How did this happen?

It goes back to a sickly academic trend called postmodernism. Michael Foucault and Jacques Derrida were major advocates of postmodernism, with its prevailing view that truth is socially constructed. What you might understand as a “fact” is actually a composite of points of view, inferences, and assumptions from your social strata. In fact, there’s no such thing as a fact. Truth is not just relative, it’s meaningless. The only thing that matters is power: who has it, and how they exercise it.

Postmodernism killed literature by divorcing it from any meaning the author might have had in mind and “deconstructing” it to uncover the underlying power plays. The disease soon spread to the arts and social sciences. When I first learned about postmodernism in the early nineties, it seemed a dead-end philosophy. That turned out to be true, but I didn’t suspect what might revive its gasping, expiring body. The salvation of postmodernism was Theory, which clarified its precepts, expanded its reach, and made it, not an academic discipline, but a Dogma and a righteous Cause.

The precepts are these:

- All knowledge is socially constructed, with language (“discourse”) as the creative agent. This includes the hard sciences and mathematics.

- All knowledge works to privilege the identity group to which it belongs by race, sex, gender, nationality, or physical characteristics.

- The identity group with the highest privilege are straight white males, who have successfully structured society to maintain their dominant position.

- All other groups (and intersectional combinations of groups) are thereby oppressed.

- The only remedy for oppression is to deconstruct white male privilege by making it stand down while other identities and “ways of knowing” achieve an equal place at the table.

- If this set of propositions seems to lack empirical evidence, well, empiricism itself is a white male invention and thereby suspect.

Do you see anything that might need to be deconstructed here?

Like most social analysis, Cynical Theories probably overstates its case, but I found it helpful and illuminating. If leftist agnostics are blowing the whistle, we’d better listen.