By now we’ve all received a crash course in infectious diseases and our hands are raw from soaping and sanitizing. (Have we ever been so aware of our hands before?) I’ve been combing the web for news, all the while reminding myself that nobody knows nothin’ yet, but I came across this bit of information that started the wheels turning in my head. I wheeled from science to theology, which is not as disjointed a track as some would think.

COVID19 is called a “novel” virus not because it’s fictional, but because it’s new. New to humans, that is; not to animals. Animals have their own viruses and are equipped to develop their own immunities, just as humans are. As human populations adapt to the peculiar RNA sequences that make up seasonal flu, so animals adapt to their own bugs and blights. These viruses almost always stay within species. But sometimes one will jump.

That’s what apparently happened in a Wuhan “wet market,” a place where live animals are sold, and often killed and eaten on the spot. A bat virus jumped to a human carrier and—in unscientific terms—dug in. Because the human immune system didn’t recognize the RNA sequencing of the foreign invader, the human became infected. And before he (let’s assume he) even knew he was sick, he had infected a number of others, and they went on to infect others, and the thing grew and grew and some people died.

One person. From just one person fever spirals out into the world, multiplying sickness and death and panic and enforced isolation and grim speculation about how many more millions will die before we acquire the immunity we need.

What makes this hyper-vigilance necessary is that the COVID19 virus is very quick: quick to spread and quick to mutate. Every flu develops singular strains, and so does this one: only quicker than most. Already it has developed at least two strains. The other cause for alarm is that it attacks human lungs and solidifies mucus, blocking air passages and causing asphyxiation. That’s why smokers, asthmatics and COPD sufferers are at particular risk.

Are you scared yet? Don’t be. Or, as beings better than I have said, Fear not. For behold, I bring you good news. We’ve already been infected by the most benevolent virus possible.

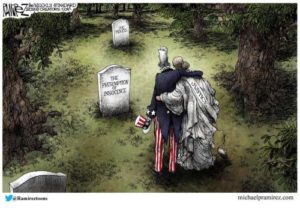

Take a deep breath. In the beginning we received our breath from God himself. And then we wrecked that ideal origin: “from one man sin entered the world.” The virus of sin is 100% contagious and in all cases fatal.

But after this had gone on for a few thousand years, long enough to prove beyond any doubt that the disease was not curable, a good contagion intervened. You might say that divine RNA jumped from heaven to earth, from God to man, just as an alien germ somehow bridged the gap animal to human in Wuhan.

The good contagion infected a handful of followers. Then a few hundred more. Then 3000 on one day. Eventually it spread, as fast as human feet and wheels and trains and planes could take it, to the ends of the earth.

I’m optimistic by nature, and at the moment I’m hopeful about how long the present crisis will last. But optimism may not be warranted; those grim predictions about millions of deaths around the globe may come to pass. But this remains: “I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full.” Death may be sown even in my small circle. But this remains: No malevolent virus can overcome the strain of divine life that infects a believer in Christ. So take heart, and believe.

around her, take stock of what she had, and be grateful for it. In time she gave hundreds of American women reason to be grateful too.

around her, take stock of what she had, and be grateful for it. In time she gave hundreds of American women reason to be grateful too. She always said—and sincerely believed—that a woman’s chief place was in the home, but she saw that place as a noble calling rather than thankless drudgery. She was, it’s fair to say, the Oprah of her day. Who can tell how many women felt lifted up and encouraged by the earnest editor of their favorite magazine?

She always said—and sincerely believed—that a woman’s chief place was in the home, but she saw that place as a noble calling rather than thankless drudgery. She was, it’s fair to say, the Oprah of her day. Who can tell how many women felt lifted up and encouraged by the earnest editor of their favorite magazine? decade:

decade:

Take “reflection.” Aside from the myth that gives “narcissism” its name, this form of idolatry is a cartoon image, the smitten individual gazing at himself in a mirror while surrounded by fluttering hearts. We’re too sophisticated for that, or almost. I’m old enough to remember a video that made the rounds during the 2004 election: John Edwards, the Democrat candidate for V-P, taking 14 minutes to comb his hair in front of a mirror just before his one televised debate. (To be fair, he possessed exceptional hair.)

Take “reflection.” Aside from the myth that gives “narcissism” its name, this form of idolatry is a cartoon image, the smitten individual gazing at himself in a mirror while surrounded by fluttering hearts. We’re too sophisticated for that, or almost. I’m old enough to remember a video that made the rounds during the 2004 election: John Edwards, the Democrat candidate for V-P, taking 14 minutes to comb his hair in front of a mirror just before his one televised debate. (To be fair, he possessed exceptional hair.)