(For the first post in this series, see “In the Beginning“)

When children in Sunday School learn about the six days of creation, they usually don’t ask why the only thing created on Day One was light. In other creation stories, solid “things” come first: rocks or water or a surging mass of elements, or the back of a very large turtle. Ancient Egyptians, Sumerians, Africans, Meso-Americans and indigenous tribes the world over would have been quite puzzled at the idea of speaking light with no obvious light source. God doesn’t get around to creating the sun until Day Four—is this not an anomaly? So I asked, when old enough to understand what “anomaly” was.

a surging mass of elements, or the back of a very large turtle. Ancient Egyptians, Sumerians, Africans, Meso-Americans and indigenous tribes the world over would have been quite puzzled at the idea of speaking light with no obvious light source. God doesn’t get around to creating the sun until Day Four—is this not an anomaly? So I asked, when old enough to understand what “anomaly” was.

We’re told that God is light; in him is no darkness at all (I John 1:5). The radiance of God is not something He whistled up to chase away the darkness, but something he is. So why say Let there be light, when light already exists, in Him?

And (a more perplexing question) where does the darkness come from? How can there even be darkness, in that blinding dynamo of Father, Son, and Spirit? Whence the cold, endless blackness that we call outer space?

And darkness was over the face of the deep. An artist has an idea for a painting. His idea includes not just the subject and composition and paint medium, but also the physical size. If he is a hands-on, muscular type, he will stretch his own canvas: purchase the stretcher boards (or make them, mitering the corners at a precise 45 degree angle), cut the fabric, staple one side of it to the center of a bar, and start pulling and stretching and stapling until the painting surface is tight enough to bounce a quarter.

Think of darkness this way: a surface, cut to precise measure and stretched over the four corners of length, width, depth, and time. The darkness is not God, for in Him there is no darkness at all. The darkness is not the absence of God, for he made it and broods over it in the person of the Holy Spirit. The darkness God creates is not the absence of light, but rather the canvas which will show light for what it is.

He is not it, but it is inconceivable without him: In his light, we see light (Psalm 36:9). (Also, He makes both dawn and dark, Amos 4:13).

Light is rich with metaphor, even when thinking about it scientifically. Isaac Newton, that great conceptual thinker who took apart and reassembled theories as some children tinker with watches, analyzed visible light as a blend of waves traveling at different frequencies. The “frequencies” are patterns that indicate how many wave crests will travel between two points in a given period of time. From his experiments with prisms, Newton theorized that six frequencies, from infrared to ultraviolet, determine the range of visible light.

Like scientific thinkers before and since, Newton could describe light but couldn’t explain exactly what it was. Though his wave theory was an improvement over the earlier “corpuscular” idea (light as tiny packets of glowing particles), it was incomplete. Waves of what? Pieces of what? The questions went unanswered for another 200 years while cutting-edge science was consumed with electricity and magnetism.

Michael Faraday, a self-taught physicist from humble Evangelical stock, proved in the 1850s that the two were related—that, in fact, a changing magnetic field produced electricity.

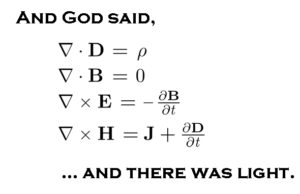

Soon after, James Clerk Maxwell theorized that vice should be versa: i.e., a changing electric field should produce magnetism. These two basic forms of energy might actually be manifestations of the same thing: electro-magnetism. Electromagnetic waves are linked in electromagnetic fields that travel through empty space and provide the energy for all kinds of chemical and physical reactions. Using known quantities, Maxwell calculated the speed of those hypothetical waves.

The result turned out to be the known speed of light.

So visible light, as nearly as we can determine, is an electromagnetic wave, like X rays and gamma rays and radio waves. They are all of the same stuff: energy. And, roughly 300 years after Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein proposed that matter and energy were interchangeable. It’s not too great a leap to say that what God brought into being on the first day was not just visible light. Let there be electromagnetism! lacks drama and wouldn’t have meant much to the ancient world. Still less would this:

But that’s the scientific description of what happens when electrical charges convert to magnetism and vice versa: energy! What happens is not just visibility or radiance, but the stuff of stars, air, rain, wind, soil, cloud, leaf, stone, and living cells. Einstein said E=mc2 (energy and matter are interchangeable). God said, Let there be light, and energy flooded the dark void that we would one day call the universe. It doesn’t come from the sun; it comes from Him. So there was no need, I can assure my sixth-grade self, to make a sun first. He would get around to that. What we get first is what we need first: matter and energy to roll into stars and cool into planets and sweep across the barren surfaces as a fertile wind.

How interesting that science agrees.

In other words, if “light” includes the entire spectrum of electromagnetic energy, Genesis 1:3 can be seen as a scientific statement. But it’s also a philosophical one: the first requirement of creation is also the first requirement of creativity, and that is vision. By his light we see light. Next, he will begin to create things to see.

Day Two – In Which Not Much Happens?

___________________________________________

- Spend some time in a very dark room, such as a walk-in closet with the door tightly shut. Stand or sit without touching anything. Try to imagine “nothing.” Is this possible? Now try to imagine light as a physical phenomenon (which it is), invading the darkness and not just illuminating but creating the objects around you. When you open the door or flip the switch, do you see things any differently?

- Ecclesiastes 11:7: Light is sweet, and it is pleasing for the eyes to see the sun (HCSB). Does this verse have more relevance after you’ve spent some time in pitch-darkness?

- If you could draw light, what would it look like?

- “I believe in God as I believe in light: not because I see Him, but by Him I see everything else.” This is a variant of a famous C. S. Lewis quote.** What does it mean to you? Can you write your thoughts in a journal or a poem?

* “A situation or surrounding substance within which something else originates, develops, or is contained,” American Heritage College Dictionary

** “I believe in God as I believe the sun has risen . . .” The last sentence of “Is Theology Poetry?” (1947)