It was all very confusing, you see. There was a scuffle, and a clash of metal, and torchlight bobbling and wobbling wildly—and then a scream. Everything skidded to a halt for the moment; all eyes went to the poor man who found himself in the middle, now sobbing and clutching the side of his head. Blood trickled between his fingers. “Find it—find it!” he yelled then, stabbing at the ground with his other hand. Seconds passed while men’s minds turned slowly over and figured out what he meant: there it was on the ground, a forlorn scrap of skin and cartilage: an ear.

(Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John: isn’t it strange that they all record this? Such an odd little detail, especially in comparison to everything else that was going down. Matthew and John were there, and Mark might have been too, if he was the young man wrapped in a linen sheet who showed up at the party for some reason. Luke would have heard the story from eyewitnesses. So maybe that’s why. Or maybe it’s because Malchus’s ear was the only casualty in a shortlived revolution, the anticipated coup that ended with a single command–)

“No more of this!”

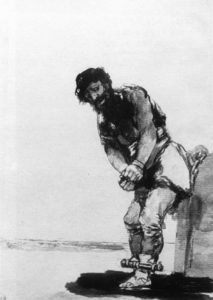

A sword lowers in a hesitant hand. The would-be prisoner takes command, but instead of fighting he’s healing, one last time. Instead of calling out the troops he’s speaking one last word as Rabbi, and the word is not about truth or righteousness or saving the world—it’s about fulfilling the scriptures.*

One sword stroke can’t stop the plan woven into the ages, but before Messiah is crushed for our iniquities, he raises a hand in a temporary halt, bends down, and picks up the ear.

He has straightened bones, restored sight to the blind and hearing to the deaf, even called a few souls back from the grave, so this act of healing is nothing to him. It’s tender and telling, though: I don’t need your swords or strategies. I want your ears.

The parade moves on and the drama plays out, but what about Malchus? And his ear?

I would like to think that, once Jesus touched it, the ear was his, good as new. And Malchus too. For the first few days, the incident in the garden was forgotten—and Malchus too. The crucifixion of the Nazarene, and the deep disappointment of those who hoped for something better, was all the news. If Jesus had stayed dead, even that news would have withered away within a generation—

But early on the third day Malchuis woke from his fitful sleep with a peculiar buzzing in his right ear. Or not really a buzz—more like a song with words he could not understand. But the sound filled him with an almost unbearable sweetness. It sang of memories and hopes, achievement and expectation above all he had ever asked or thought. His mind, lately roiled with memories of torchlight, flashing swords, and searing pain, quieted itself like a weaned child with its mother, listening. He put an arm around his sleeping wife and listened. He shushed her querulous complaints and listened. His heart warmed with compassion for his difficult son and sickly daughter while listening. When the sun was fully up and the city shook itself awake and rose to the first day of the week, the song faded like a dream.

By noon rumors were flying in the electrified air. Several people had visited the empty tomb and seen the limp winding clothes with their own eyes. The scribes and priests were quashing rumors left and right: pay no attention; it’s a trick; move along; nothing to see here.

Malchus, a loyal Levite, had served the high priest all his life—first Annas, then Caiaphas. He knew them well, and never thought to question an authoritative word from either of them. That day, authoritative words were ringing off the walls: It’s a trick! It’s a lie! It never happened!

But when Malchus first heard the news from a fellow servant, everything made sense, especially those puzzling scriptures the Rabbis loved to argue over. Messiah’s last touch, on the ear he restored, flamed to life again. The sweet song spun off words. He was filled with a joy inexpressible and full of glory.

What happened to Malchus? Probably an ordinary span of days ending in ordinary death. The song in his ear would diminish with age until he couldn’t even remember it, but if that life was planted in him, he is hearing it now.

He who has an ear to hear, let him hear!

_______________________________________________

*Matt. 26:53-54. “Do you think that I cannot appeal to my Father, and he will at once send me more than ten legions of angels? But how then should the Scriptures be fulfilled, that it must be so?”

Mark 15:49-50. “Day after day I was with you in the temple, and you did not seize me. But let the Scriptures be fulfilled.”

Luke 22:37. “For I tell you that this Scripture must be fulfilled in me: ‘And he was numbered among the transgressors.’ For what was written about me has its fulfillment.” (Luke records this earlier, in the upper room, but it’s in the context of a conversation about swords.)

John 18:11. “Shall I not drink the cup the Father has given me?”