In Chapters 1-4, we situate ourselves in a time and place: modern Britain sometime in the 1950s, with the memory of World War II’s devastation fresh and vivid.

The action takes place at three fictional locations: Edgetow, a university town similar to Cambridge, but smaller; St. Anne’s-on-the-Hill, a nearby village; and Belbury, a village in the opposite direction, currently undergoing a process of modernization. The plot is immediately tangled in University politics, so it helps to know that the University of Edgetow is composed of four separate colleges, each with its own administration and disciplines . Bracton College is the one that will concern us, because of the characters associated with it. In these first chapters Lewis, like any good novelist, is introducing his major characters and moving the conflict elements into place—like setting up a chessboard and marking out a strategy. The problem for contemporary readers is that he takes an awfully long time to do it and assumes a literary and history background that most Americans don’t have. So here, with the help of notes obtained from the Lewisiana website, are a few pointers.

CHAPTER ONE: SALE OF COLLEGE PROPERTY

1.1 Jane Tudor Studdock, a thoroughly modern post-war young woman, is at the beginning of a marriage that has already proved disappointing. The words she recalls in the first paragraph are from the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, the traditional ringing tones of which contrast sharply with Jane’s “improved” attitudes. She’s not a believer, but Anglicanism was the state religion (still is) with some authority over civil institutions like marriage. The clash between tradition and fashion sets Lewis’s theme, and Jane’s disturbing dream puts the plot in motion. She and her husband Mark will be the contrasting poles between which the action will shift and build.

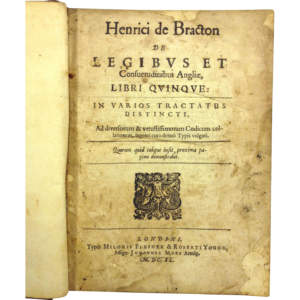

1.2 Mark Studdock is intent on advancing his academic career. He’s a sociologist, a relatively new field of study at the time, and Lewis doesn’t seem to think much of it. Mark’s conversation with Curry shows how the academic world (then and now) is obsessed with position: the whole of point of an academic career is levering oneself into a cushy sinecure where one can collect a handsome salary without doing a lot of work (nothing has changes). Henry de Bracton (ca. 1250), for whom Mark’s college is named, was the author of a book on common law, in which he argued that secular authority is subject to the law. This also plays into Lewis’s theme. If you haven’t read Out of the Silent Planet, it’s important to know that Dick Devine (Lord Feverstone), whom Curry mentions as the one who got Mark his position, is the same Devine who accompanied Drs. Westin and Ransom on their trip to Mars.

1.3 This is a lovely section that you can feel free to skip, because there’s a lot of history and atmosphere that you may not be susceptible to at this point. Suffice it to say that Bragton Wood, a small enclosure within the college, is redolent with mystery as well as history, because it’s the location of “Merlin’s well.” Merlin is not just a character in the Arthur legends, but rather the character around whom the legends collected. The earliest references to him (ca. 800 AD) suggest that he had no father, giving rise to the rumor that he was the devil’s son. More of this later. What Lewis suggests in this chapter is that the College, feverishly modernizing, is sitting on a vast reserve of ancient power and knowledge that will not be swept aside.*

1.4 Lewis draws this chapter out so long it’s like you’re sitting in on an actual college meeting! But it’s worth reading for the clever way in which the “progressive” element maneuvers the fellows into voting to sell Bragdon Wood–a sale they would never have approved on a straightforward vote. This section also introduces the National Institute of Co-ordinated Experiments, or N.I.C.E., the collective villain of the piece. (Lewis obviously named the Institute with the acronym in mind, but it’s worth a mention that the UK’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, a division of its National Health Service, also takes the acronym NICE.) Why does the N.I.C.E. want Bragdon Wood? That’s the question . . .

1.5 Introducing Dr. and Mrs. Cecil Dimble, sympathetic characters who already have a connection with Jane. They happen to live on Bracton College property, though Dimble teaches at another college. The couple have recently learned that their lease is not being renewed, no telling why. Notice how the tension slowly builds as change comes quickly to this sleepy little town, and how the Arthur legend comes up again in the conversation over tea.

*The heedless modernization Lewis saw in the fifties–or actually after the first World War–came into its own during the sixties. He pictures the change being wrought by an axis of government and academic bureaucracy; he might not have foreseen the wave of radicalism that hit college campuses in the mid-sixties, fueled (in America) by the Civil Rights movement and the VietNam war. But it was brilliant of him to perceive the corruption of the University as the eventual collapse of civilization.

CHAPTER TWO: DINNER WITH THE SUB-WARDEN

2.1 Non-olet is Latin for “it doesn’t stink,” ascribed to Emperor Vespasian’s reference to tax proceeds from public toilets. The Sub-warden, remember, is Curry; the college bursar (treasurer) is Busby: these are two Bracton hot-shots who will be edged out of prominence as Lord Feverstone circles like a shark around Mark. Notice his mention of Dr. Westin, the antagonist of Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra. The “respectable Cambridge don” is Dr. Ransom, hero of those books. Feverstone’s talk of “taking charge of our destiny” is exactly what some contemporary scientists–as well as futuristic entrepreneurs like Elon Musk–mean by taking control of evolution. The catchword today is “transhumanism.” The theme is coming clearer now, and Mark will not be able to claim that he wasn’t warned.

2.2 and 2.3 Jane has another dream; her fear grows even as she despises herself for it. Mark is totally out of his element with her. We will see them together only one other time (briefly) during the course of the novel, and it’s interesting analyze their relationship here: what are the danger signs you see? Have you noticed anything similar in couples you know? Remember that Jane and Mark are the two poles of the narrative: the action will shift back and forth between them, with ever-growing light and ever-increasing darkness.

2.4 Mark motors to Belbury, N.I.C.E. headquarters, with Feverstone: “a big man driving a big car to somewhere where they would find big stuff going on. And he, Mark, was to be in it all.” Already we’ve seen Mark’s hunger to be in the inner circle, a lust that goes back to high school for almost everybody—I can certainly sympathize. Incidentally, Lewis’s description of the sights may go on too long here, but I love his hinting at the ineffable potential of passing scenery: it’s like peeking into lighted windows as you walk by them. Belbury might have been based on Blewbury, a village south of Oxford that became the site of the first nuclear reactor in Europe.

CHAPTER THREE: BELBURY AND ST. ANNE’S-ON-THE-HILL

3.1 and 3.2 Out of the frying pan, into the fire, though Mark recognizes only that he must find his way to the real power source here, just as he did at Bracton College. He is first introduced to John Wither, Deputy Director of N.I.C.E. who can’t seem to direct a cogent thought. William Hingest, whom Mark knew at Bracton, strikes the first sour note. Crosser and Steele are the kind of mediocre talents that bureaucracy thrives on, and Professor Filostrato may be one of the inner circle.

3.3 Meanwhile, at St. Anne’s, Jane meets Camilla Denniston (whose husband was mentioned in 1.2 as Mark’s rival for his fellowship), and Grace Ironwood, to whom she forms an immediate dislike. Why? What is it in Jane’s character that reacts negatively to Miss Ironwood’s?

3.4 Mark’s introduction to “Fairy” Hardcastle, one of Lewis’s more vivid characters. She’s chief of the Institute’s police, and why should a government institution need its own law enforcement? That should raise questions right away, as it does for Dr. Hingest, but Mark falls in with the line that the work is too vital, though controversial, to lack protection. (By the way, did you know the the U. S. Department of Education has its own swat team? Would it be amiss to wonder why . . . ?)

3.5 The real trouble begins.

CHAPTER FOUR: THE LIQUIDATION OF ANACHRONISM

The title is a mouthful, referring to modernism’s goal of purging the past, along with its obscure symbolism and burdensome rules. This is a major theme of The Abolition of Man (see my first post on that a week from today).

4.1 and 4.2 The N.I.C.E. is demonstrating the swagger of Nazi hordes, an all-too-recent memory. Mrs. Dingle’s description of their mowing down the woods compares to the murder of the trees from Narnia’s Last Battle. I’m intrigued by her question, “do human beings really like being happy?” A lot of us certainly enjoy being angry, or feeling put upon (speaking for myself).

4.3 Mark shares a morning stroll with the Reverend John Straik, whose presence at the Institute is a mystery. Isn’t modern science supposed to root out fire-and-brimstone religious fanatics such as this? I can’t think of a contemporary parallel to Straik (can you?), but he’s not the only one to mold the image of Christ to his own inclination. Softer forms of Christianity have played in to hands of power often enough, as the National Church did in Hitler’s time. Notice Mark’s acute embarrassment “at the name of Jesus”—love it! The name of Jesus was, is, and will always be offensive: a “stone of stumbling, and a rock of offense.”

4.4 Foul play; your suspicions should be raised. I love the last paragraph!

4.5 All Jane wants is “to be left alone.” This was Lewis’s own desire, as described in Surprised by Joy. Is this reasonable? Is it possible?

4.6 The proposed “liquidation” of Cure Hardy reflects what is going to happen to Bracton Wood. It goes on a little too long; you can get the sense by skimming. Some redeeming aspects of Mark’s character emerge here, and a good thing too; major characters need to be somewhat sympathetic. What are these redeeming features? Notice how his field (sociology) concentrates on group identity rather than individual, exactly as political correctness does today.

4.7 This scene is just devastating: the colleges progressives have sown the wind and now reap the whirlwind of mindless destruction: the “liquidation of anachronism,” indeed. Notice how Mark is being maneuvered from afar—the inner circle he craves membership in is advancing him like a chess piece.

That’s the challenge as Christians, isn’t it? Our natural desire is to fit in but God has arranged it so that we must remain in this world for a time but not fit in. There is that constant tension which can produce a feeling of alienation because it makes us feel on the outside.

I have to remind myself that I am on the inside, just not here; the “Persons” I am surrounded by are invisible for now.

I did not realize you were starting so soon so I have spent the weekend reading the first four chapters (actually five-might has well get a jump on next Friday.)

Firstly, I am already feeling incredibly tense because I see the darkness gathering around Mark. Yet at the same time I’m impressed with how forth right he is, demanding that someone give him a concrete answer about whether he’s got the job and what exactly is the job, if he does have it at N.I.C.E. I can’t help imagining myself in the same situation; I’d be afraid to show my ignorance and would hope that it all became clear by itself.

The pompousness and pretension he experiences at the hands of the others there is all too familiar. Do the others really know what’s going on or are they all pretending to? The old man, Withers, drives me crazy with his babbling incoherence. I read this book a long time ago and I can’t remember whether this is contrived on his part or if he is really not “with it”.

It’s with relief when I read about Jane with the Denniston’s and Miss Ironwood. St. Anne’s is a shining oasis. A safety zone.

As usual Lewis’ insight into human nature just charms me. I love reading both Jane and Mark’s thoughts and recognizing how much in common I have with them.

And as you have suggested, I think that he has nailed how our educations system seems to be intentionally destroying actual learning by wanting to get rid of anything “anachronistic”. Hence histories are revised to conform to modern values and identity politics. I am currently reading The Abolition of Britain by Peter Hitchens. He describes a lot of what Lewis writes about being realized in England since WWII.

I’m enjoying your comments. There’s so much just there in the first four chapters. I look forward to what you say about the next.

Sharon, Thanks for catching up! You’re so right–there’s a lot in the first four chapters. I believe this is one of Lewis’s best-structured novels, in spite of the many discursive paragraphs. I don’t admire Mark so much in these chapters: he’s forthright, but mostly in his own interest and drive to get ahead. He’s a social climber with a gift for finding the true movers and shakers, but he also knows not to grovel or flatter. I can sympathize with him, though. I understand the lust for being on the inside, and I think most of us share it to some degree. In a way it’s not entirely bad–just part of the natural need everyone has for belonging.