One Sabbath, when he went to dine at the house of a ruler of the Pharisees, they were watching him carefully. And behold, there was a man before him who had dropsy. And Jesus responded to the lawyers and Pharisees, saying, “Is it lawful to heal on the Sabbath, or not?” Luke 14:1-3

Even though they don’t like him they’re still inviting him to dinner. This is a Sabbath-meal event, attended by the whole town apparently, because someone gets in who has “dropsy,” or edema. (This might have been understood to be a dreaded “skin disease” of the type relentlessly described in the Law, thought dropsy is not considered a skin disease today.) The guests—if we can presume to put thoughts in their heads—may be thinking, Ew. Who let him in? That bloated flesh is a sorry aid to digestion. He has some nerve . . . And the man does have some nerve, but he also has some faith, putting himself in adverse circumstances so Jesus will notice him.

Even though they don’t like him they’re still inviting him to dinner. This is a Sabbath-meal event, attended by the whole town apparently, because someone gets in who has “dropsy,” or edema. (This might have been understood to be a dreaded “skin disease” of the type relentlessly described in the Law, thought dropsy is not considered a skin disease today.) The guests—if we can presume to put thoughts in their heads—may be thinking, Ew. Who let him in? That bloated flesh is a sorry aid to digestion. He has some nerve . . . And the man does have some nerve, but he also has some faith, putting himself in adverse circumstances so Jesus will notice him.

Or, since the Pharisees are “watching him carefully,” this may be a setup. They might have found the man and dragged him into the house to as a test case, instead of letting him wait until sundown and asking Jesus to heal him without legal controversy. Who knows?

Whatever the plan, he sees through it and cuts to the quick. The wording suggests that Sabbath observance is already a topic under discussion: “It is lawful to heal on the Sabbath, or not?” Or, put another way, Can you people see the difference between the letter of the law and the law’s intent?

No answer. Of course. Interestingly, they know he can heal, they know he will heal and they also know how they’ll hold it against him–laying up his creative, restorative divine acts as evidence for condemnation. Who does he think he is, after all?

But more to the point, perhaps, is who they think they are.

“You treat animals better than you do your brothers,” he says, after healing the man (easy as that—healing is almost an side event now!). “And another thing: I notice how when you take your places at the table you negotiate the best positions for yourselves. Suppose I got married, and invited you all to the wedding dinner.” (Their ears perk up, friend and foe alike—is he planning a big announcement?) “Let me offer a word of advice: don’t presume on your position and choose the best place. Imagine your embarrassment when the host marches up and tells you to move, because a more distinguished guest has arrived. Someone like—oh, that serving girl over there.” A ripple of merriment runs through the friends and bystanders, who love the way he turns the established order upside-down. While the serving girl blushes, a murmur of outrage from the establishment runs in the opposite direction.

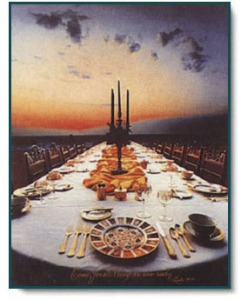

“. . . Rather, when you come to my banquet, choose a low place for yourself. Then I may come and say, ‘Friend, move on up!’ And you’ll be exalted among the company instead of humiliated. Remember the saying? ‘Some are last who will be first.’”

A guest across the table, perhaps in the interests of making peace (or perhaps because he’s had a bit too much to drink), lifts his cup and says, “How happy are those who break bread in the kingdom of God!”

“Do you think so?” Jesus looks around the table, his eyes sizing upon and evaluating each man in turn. One by one, they feel themselves evaluated; are outraged, embarrassed, nonplussed. “A certain wealthy man planned a great banquet, the event of the season. You’d think his neighbors would be counting the days, wouldn’t you? Eagerly anticipating? Well, when the great day finally came, with the meats roasted and the bread baked and the wine decanted, the man sent his trusted servant out to bring them in.

“Everything is ready,” said the servant at the first house. “Come and feast!”

“’So soon?’ replied the householder. “What bad timing! I just bought a field and have to go test the soil to be sure I got my money’s worth. Please excuse me.’

“Shouldn’t he have done that before buying the field? Oh well. Scratching his head, the servant proceeded to the next house and almost collided with the owner, who was striding out with a whip in his hand. ‘Greetings, sir! My master sent to tell you the feast is ready. Please come.’

“The man paused, with an impatient frown. ‘What feast? Who is your master, again? Never mind—tell him I can’t come. I just bought a yoke of oxen and must plow the lower forty before sundown. Sorry.’

“At the third house, the servant knocked and knocked before the owner finally came to the door with his hair all awry and a sheet tucked around him. ‘What’s that? A banquet? That’s impossible! I mean, I just got married and, well, you know . . .’

“On it went, house after house, refusal after refusal. The servant finally returned home, alone. What should have been a joyful procession of happy friends and neighbors was a single dejected, sweaty individual who couldn’t help wondering if there was something wrong with him.

“’What’s this?’ cried his master. ‘Where is everybody?’ While the servant ticked off all the excuses he’d heard that day, the master’s face darkened. ‘All right then, here’s what you do: go to the hovels and the dives, the brothels and the market places. Broadcast my invitation like barley and wheat. My house will be filled—but not one of those invited to my feast will taste a morsel of it!’”

His listeners, or at least some of them, can’t escape the feeling that he is talking about them—the householders, the property owners, the well-heeled and well-married. And he is talking about himself, an itinerant preacher without a foot of ground to his name, as if he were the richest man in town with a house so large it can hold every beggar, slave and whore in the land. He has that air about him: women supply his meals, but he speaks as though he owns the cattle on a thousand hills. As for this story—well, it’s just a story. Wealth is a sign of God’s favor, after all; they have lived all their lives on the inside.

So . . . why do they feel shut out in his presence, as though they should be the ones knocking, pounding, pleading to get in?

For the original post in this series, go here.

Next>